Charlemagne (742-814), known as Karl the Great in German, is well known as the first ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, a successful military commander and a generous patron of the arts. Although not often considered a part of his legacy, he also was an accomplished gardener.

Since my recent trip to Germany, I’ve been reading the article of the day on the German Wikipedia page. A link in an article about Charlemagne led me to the list of plants he (well, his managers) grew. I was intrigued by the number of plants and that many of them grow here in the Lowcountry.

An impressive number of useful plants were cultivated on his imperial estates throughout France, Germany and northern Italy. The sole surviving copy of the “Capitulare de villis vel curtis imperii,” roughly translated as “A Chapter on Farmsteads of the Imperial Court,” lists 99 herbs, medicinal plants, vegetables, fruits, nuts, dye and fiber plants, grains and beans.

This handwritten Latin manuscript is an important primary source of gardening information from the early Middle Ages, as well as fascinating horticultural history.

Since the author did not record the date, historians estimate it was created between 771 and 812. An English translation is available from the University of Leicester (http://bit.ly/1KEz1yV).

The main horticultural paragraph (number 70) lists the common names of 73 herbaceous plants and 17 perennial trees and shrubs. Fourteen of these plants cannot be precisely identified, since there are two (or even three) plants known from the region at that time with the same name. (Botanical names did not exist until centuries later and were not standardized until the 1700s.)

Unfortunately, the list of plants is not included in the English Wikipedia page, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capitulare_de_villis, but the German, Spanish, and French pages have the Latin common names and botanical names.

The annual plants include 29 medicinal plants, 22 vegetables, 13 herbs and spices, four legumes, three flowers (Madonna lily, Italian gladiolus and dog rose), common madder (which produces a red dye) and teasel (used to card wool).

Of course, some plants had multiple uses. Sage, anise and coriander were both herb and medicine. Southern wormwood was medicine and air-freshener.

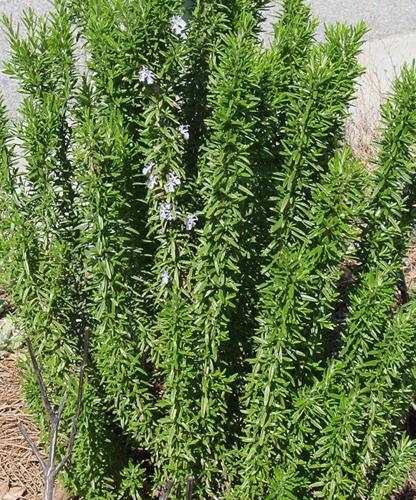

Other plants had different uses in the Middle Ages than today. Fenugreek was recommended for skin diseases. Rosemary was used in northern Europe to treat toothaches, wounds, eye floaters and six other ailments.

Greater burdock, a large perennial weed in cool climates, was a root vegetable.

Interestingly, most of the vegetables are still commonly eaten today. The largest group are from the onion family: onion, bunching onion, shallot, leek, chives and garlic.

The next sizable group is the cabbage family: cabbage, turnip, radish, arugula and watercress. Cucumber, cantaloupe, celery, carrot, parsnip, lettuce and Swiss chard also were grown, as well as pea, chickpea and broad bean.

Charlemagne grew a variety of woody perennials, consisting of 11 fruits, five nuts and bay. The fruits are apple, pear, peach, plum, cherry, mulberry (for wine), fig, quince, medlar (a type of hawthorn) and sorb (Sorbus domestica), a European relative of mountain ash that was cultivated and spread by the Romans.

The 11th fruit has been identified as either apple or sour orange. The nuts are chestnut, hazelnut, almond, pine nut and walnut.

Apples and pears seem to have been the most important fruits. Additional notes about apples refer to “sweet ones, bitter ones, those that keep well, those that are to be eaten straightaway, and early ones.”

Four apple varieties are named, but, unfortunately, they are unknown today. “Of pears, they are to have three or four kinds: those that keep well, sweet ones, cooking pears, and the late-ripening ones.”

Certainly, the list of vegetables and fruits illustrates great variety in the diet of those fortunate enough to live at court. This sounds much more appealing than the meat and bread often associated with medieval cuisine.

I also was surprised that the importance of good seed was recognized so long ago. Paragraph 32 says, “That every steward shall make it his business always to have good seed of the best quality, whether bought or otherwise acquired.”

Other paragraphs in the manuscript cover field crops and animal husbandry. Crops mentioned include wine grapes, wheat (as flour), two kinds of millet, barley (as malt for beer), flax, hemp and dyer’s woad, a blue dye plant.

The animals to be raised on each estate were dairy and meat cattle, oxen, horses, swine, sheep, goats, chickens, geese, dogs, fish and bees. In addition, Charlemagne wanted “swans, peacocks, pheasants, ducks, pigeons, partridges, and turtledoves for the sake of ornament.” Hawks and falcons were kept for hunting.

Charlemagne’s amazing gardens orchards and vineyards reveal a bountiful horticultural enterprise that flourished during what was once called the Dark Ages.

Anthony Keinath is professor of plant pathology at the Clemson Coastal Research & Education Center in Charleston. His expertise is in diseases of vegetables. He also is an avid gardener. Contact him at tknth@ clemson.edu.